—A report from the field by Kirsten Southwell, Frontier Fellow.

When asked, “So what are you going to do in Utah?,” my response was, “Something about rocks.”

The vagueness was both a blessing and a curse. This was my first artist residency, and the lack of a plan left me worried that I wouldn’t be able to perform. In reality, I could not have ever premeditated the project that organically grew out of my time in Green River.

A repeating pattern made from Google Earth images of land use around Utah (left). Rocks I collected, shaped, and polished from the Crystal Geyser (right).

A repeating pattern made from Google Earth images of land use around Utah (left). Rocks I collected, shaped, and polished from the Crystal Geyser (right).

I started my learning about the raw materials native to the area, specifically in the context of the mining history of the region concerning coal, uranium, salt, gypsum, and potash. I was obsessed with how mines and tailing ponds looked from above—open wounds and unnaturally colored geometric ponds. I can’t fully articulate the source of my fantastical interest in mining, but I appreciate how Lucy R. Lippard explains her preoccupation with gravel pits:

“Like archaeology, which is time read backwards, gravel mines are metaphorically cities turned upside down, though urban culture is unaware of its origins and rural birthplaces… Their emptiness, their nakedness, and their rawness suggest an alienation of land and culture, a loss of nothing we care about.”

— Undermining: A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West

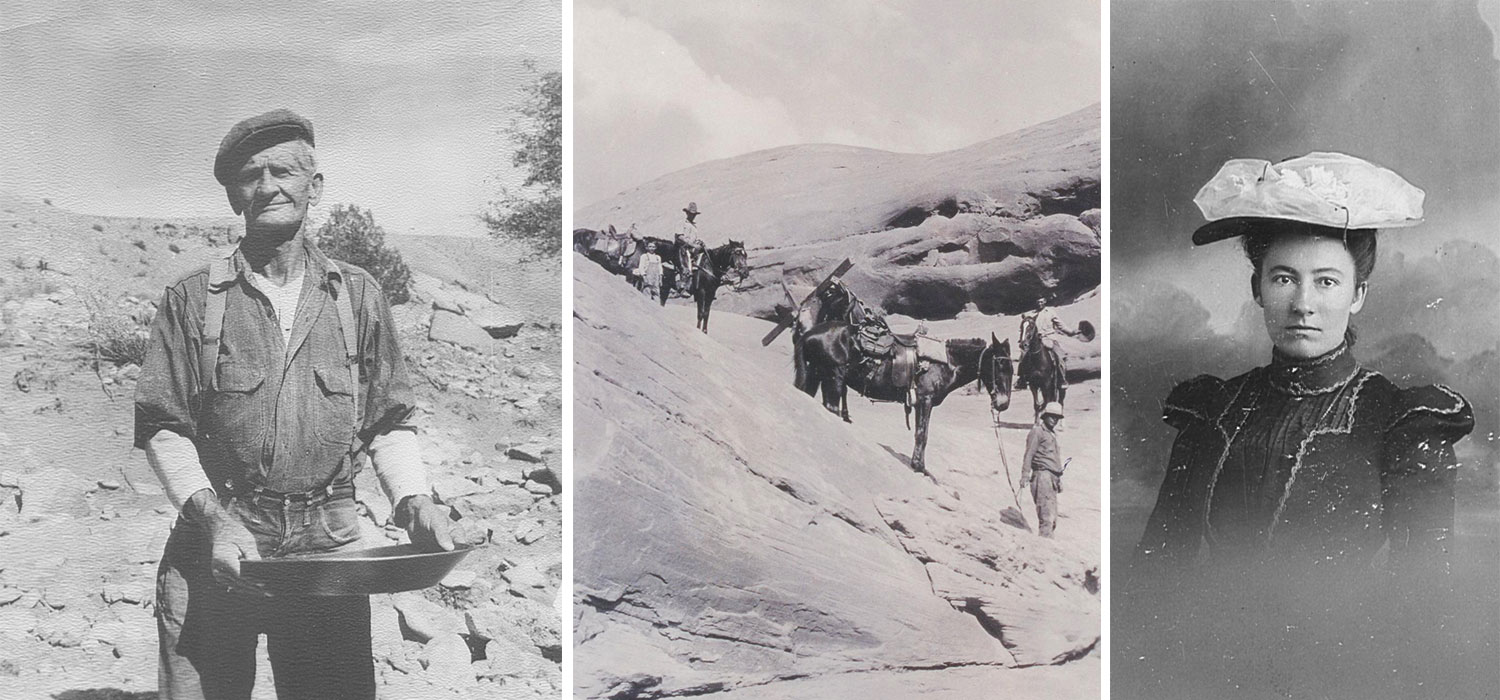

Inspirational images from the John Wesley Powell Research Center and Archives.

Inspirational images from the John Wesley Powell Research Center and Archives.

The story of mining is the story of civilization. In modern times, the imagination for what is below continues to encourage the industry to thrive, both shaping and being shaped by the geological constraints and cultural demands of our world. This is especially true in the Colorado Plateau of Utah—where Green River sits—as a region of exceptionally rich natural history and diverse human interest. Here, we can see the triumphs and failures of the impact of mining in both the people and environment.

Collecting potash from the Intrepid Potash Ponds (left) and collecting uranium from a mine off Interstate 70 (right).

Collecting potash from the Intrepid Potash Ponds (left) and collecting uranium from a mine off Interstate 70 (right).

I visited mines to take pictures and collect specimens. I tried using different natural materials I collected to manipulate textiles: finding rusted metal for shibori, dissolving potash into mordant, applying salt crystals to wet dyed fabrics. While my experimentation veered into abstraction, I grounded myself by visiting the local John Wesley Powell museum archives, the Utah Natural History Museum, and a trip to the Western Railroad and Mining Museum in the neighboring town of Helper to attempt to understand what natural forces make the Colorado Plateau so rich and how what is underneath has shaped life above ground.

Specimens I collected during my fellowship. Left to right: not sego lilies, potash, coal dust, geyser rock, snake corpse, Morrison Formation, and not uranium.

Specimens I collected during my fellowship. Left to right: not sego lilies, potash, coal dust, geyser rock, snake corpse, Morrison Formation, and not uranium.

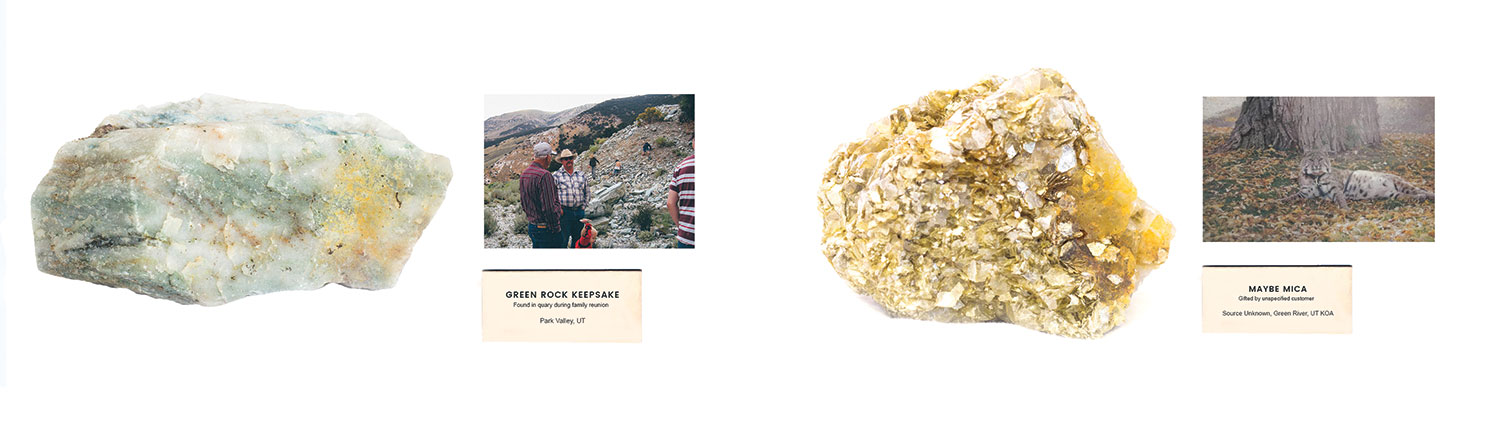

Pulling from my own professional background in the museum world, I decided that my project would be a digital museum exhibit called The Romance of Mining. It blends fact, fiction, and narrative to explore the financial and interpersonal value of natural resources, the lure of the mine, and our thirst to control our surrounding landscapes. All of my experiments and specimens are artifacts in my exhibition, including a quilt, a dress, a portrait series, and select pieces from local’s personal rock collections.

Abandon the Grid quilt, which used mined materials to influence the dying of the fabrics (left). Mine pattern dress (right).

Abandon the Grid quilt, which used mined materials to influence the dying of the fabrics (left). Mine pattern dress (right).

The work I made is only half the story. The project was very ambitious for just one month, and I felt endlessly exhausted. My sanity, positive attitude, and do-it-to-it spirit would have been completely impossible if not for the social backbone and community warmth from the people of Green River.

Mining portraits. Richard (left) Katie (middle) Armando (right).

Mining portraits. Richard (left) Katie (middle) Armando (right).

The people of Green River, and especially the Epicenter staff, are very generous. It’s one thing to move to a small town for a month, it’s another to move to a small town with an awesome group of thoughtful and hilarious people that will endlessly entertain and engage you. I have a tinge of sadness knowing that I won’t be here to tailgate for the next City Council meeting or scarf the ‘za with you all of you again soon, but am humbled to have met people so incredibly dedicated to their community.

Epicenter staff Bryan, Katie, Ryan, and JD with resident barkitect, Rusko, in a gypsum quarry in the San Rafael swell.

Epicenter staff Bryan, Katie, Ryan, and JD with resident barkitect, Rusko, in a gypsum quarry in the San Rafael swell.

On that note, I was also impressed with the respect that Epicenter has garnered here, and that respect seemed to be reflected onto myself by extension. The people that participated in my project were bringing me into their homes without question, sometimes without even meeting me in person. These were some of my favorite moments, watching people light up while talking about the rocks they decided to pick up a rock—out of an endless world of rocks—and bring home.

Life after this residency is a bit of a mystery to me. I have a little peace knowing I will get to continue wrapping up this project from home, and I hope that the emotional and mental effort I put into developing my artistic practice will continue. I look forward to following the work that is continues to happen here in Green River, and am so excited for all of the future fellows to fearlessly dive in and get weird. I’ll be leaving behind some rocks for you, and a cheat sheet of all the best mines.